A Question of Time

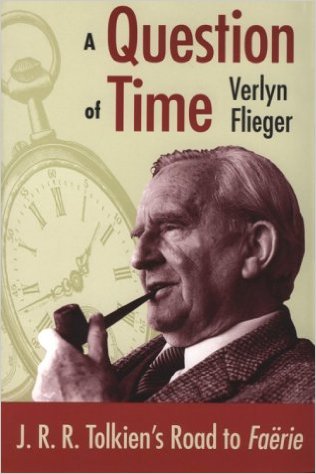

Flieger, Verlyn. A Question of Time: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Road to Faërie. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-87338-574-8, $35.00.

(This review originally appeared in Mythprint 35:3 (#192) in March 1998.)

Reviewed by Douglas A. Anderson

Verlyn Flieger’s first book, Splintered Light: Logos and Language in Tolkien’s World, was published in 1983. Her second book has been a long time coming, having finally appeared fourteen years after the first. An early version of one chapter in the new book appeared in Mythlore as long ago as 1990, but clearly Flieger’s topic is one that needed a long gestation period. And the end result is certainly well worth the wait.

Basically, Flieger’s new book explores the interrelation and evolution of the themes of time, dream, and ‘faërie’ throughout Tolkien’s major works. It is a selective approach, emphasizing The Lord of the Rings, Smith of Wootton Major, and the unfinished chapters of “The Lost Road” and “The Notion Club Papers”. As precursors to Tolkien, and as possible influences, Flieger also explores some relatively unknown literary and scientific writings of the 1890s through the 1930s. Of the literary writings, she illuminates for us the works of George Du Maurier, particularly his first novel Peter Ibbetson (1891), as well as two plays by J.M. Barrie, “Mary Rose” and “Dear Brutus”, and John Balderstone’s play “Berkley Square”, based on an unfinished story by Henry James. The main non-literary work she sees as a large influence on Tolkien is An Experiment with Time by J.W. Dunne (1927), an abstruse consideration of the hypothetically intersecting roles of sleeping dreams and time (past or future). Dunne’s theories, now largely discredited, were a considerable phenomenon in the 1930s. A further book discussed by Flieger is An Adventure (1911), a purportedly true account of two women who experienced a time-slip in the gardens of the Trianon and spent an afternoon in the past.

Flieger finds in these writings, as well as in Tolkien’s own works, a number of the intellectual currents of the time, expressed variously and perhaps in contradistinction to some of the more recognized modes of the times, but which are there nevertheless. This is a further elaboration upon the theme of time as mentioned in the book’s title, for Flieger presents an emphatic defense of Tolkien as a writer of his own time, profoundly concerned with the cultural history of the time in which he lived.

Without delving into the details (and several of them, particularly those relating to the time theories of J.W. Dunne, are complex enough that no simplification could suffice), I have to say that I experienced while reading this book a number of nearly breath-taking illuminations on Tolkien and on how his mind worked. One hardly expects to be convinced of an entirely new approach to understanding parts of The Lord of the Rings via the interweaving of dreams and precognition, but Flieger accomplishes just that. And all throughout the book I found little epiphanies exploding into some larger significance, with further moments of resonance applicable throughout the range of Tolkien’s works. This book is one of the more serious considerations of Tolkien as a thinker, and I would urge anyone interested in the mind behind the creation of The Lord of the Rings to read this book.

On a much less significant matter I am compelled to say that, physically, the design of the new book is unfortunate. The outer margins are too generous, while the text itself curls into the central gutter of the book, making it difficult to read unless the book is fully opened and flat. The dust-wrapper design is also unflattering: a simplistic design with text and photos in unbalanced sizes. However, the paper on which the book is printed, and the binding, are first-rate, as is the text inside — which is of course the main interest in the book.

If I am to find any real flaw in the text itself, it would have to be in the approach and the selectivity of the coverage. I really want to know more about the phenomenon of Dunne and his influence upon literature. As early as 1944, the critic Edward Wagenknecht was remarking upon a literature based upon Dunne and his theories, one that in England “has now grown into a very respectable small industry.” Wagenknecht cites several examples, including John Buchan’s The Gap in the Curtain (1932), which seems to be a good candidate for Tolkien to have read, but it isn’t covered by Flieger.

And despite the abstruseness of Dunne’s theories, I wish Flieger would have explored further some of Dunne’s books beyond An Experiment with Time: This Serial Universe (1938), The New Immortality (1939), and Nothing Dies (1940). It seems to me that some elements of Dunne’s “serialism” — at least from This Serial Universe — found their way into Tolkien via his use of the theme of reincarnation. Flieger touches upon this briefly, but leaves the topic itself mostly unexplored, and this feels to me like an omission. (In Flieger’s defense it must be admitted that Dunne’s books subsequent to An Experiment with Time were hardly well-received — and even Dunne’s old friend H.G. Wells referred to them as “an entertaining paradox expanded into a humorless obsession.”)

Still, these are very minor squabbles. A Question of Time is a first-rate exploration of Tolkien’s obsession with time, and it has earned a secure position on the small shelf of absolutely essential books about Tolkien.