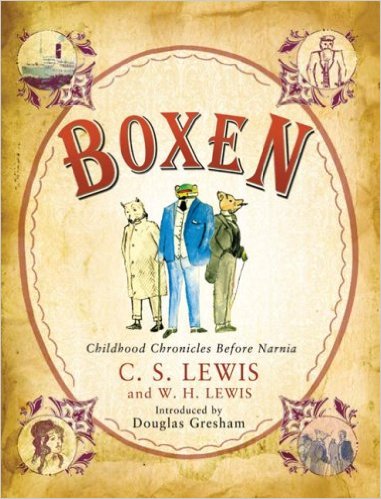

Boxen

Lewis, C.S. and Lewis, W.H. Boxen. Ed. Walter Hooper. London: Collins, 1985. 206 pp. ISBN 0-00-21508-4.

Reviewed by Nancy-Lou Patterson

[This review originally appeared as “Action, Comedy, Invention” in Mythlore 12.1 (#43) (1985): 39-40.]

It would be hard to imagine a work more long-awaited than this: its existence was revealed by Lewis himself in Surprised By Joy (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1955) as he described the “blessing” of his relationship with his brother Warren. Their earliest works were drawings: “His [Warren's] were of ships and trains and battles; mine, when not imitated from his, were of what we both called ‘dressed animals’” (13). Of his own drawings, Lewis comments, “there is action, comedy, invention,” but not “a single line drawn in obedience to an idea, however crude, of beauty” (14). These descriptions can also apply exactly to the written juvenilia now published (30 years after their first public mention and more than 75 years after their composition as Boxen).

The second mention of Boxen is from the hand of Warren Lewis: writing of life in Little Lea, their Belfast home, he recalled in his edition of Letters of C.S. Lewis (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1966), “together we devised the imaginary country of ‘Boxen’ which proliferated hugely and became our solace and joy for many years to come” (2). The “Boxen” materials, which include a variety of fragments, and a later tongue-in-cheek “Excyplopedia Boxonia” composed by C.S. Lewis in 1927, are now in the possession of the Marion E. Wade Collection at Wheaton College, Illinois, and of the Rev. Walter Hooper. At least three portions do not appear in the present published volume: “the fragment Tararo, The Life of Lord John Big, and Littera Scripta Manet.” Hooper tells us tantalizingly that “I hope to publish them when the time is right for a second volume of Boxen stories” (Boxen 18).

The works we do have in print have been edited with Fr. Hooper’s usual industry into two appropriate portions. The first, “Animal-land,” contains a series of fragments and chronicles, about thirty-six pages of them. About these, Hooper warns “I dare say there will be those who will find the early writings tedious. If you are one of the latter I suggest you stop reading this and go directly to the … ‘novels’” (9). The second and much larger portion contains these “novels”––”Boxen, or scenes from Boxonian City Life,” “The Locked Door,” and “The Sailor.” In “Boxen” the young author details the political machinations by which Polonious Green, a parrot, attempts to bring about the election of a new “Clique” in the dual Parliment of the Kingdoms of Boxen, whose monarchs are the Rajah of India, Hawki V. and the King of Animal-Land, Benjamin VII (a rabbit). These monarchs are young and addited to the theater, and rather in awe of the Little-Master, Lord Big (a frog). Readers can see in the ‘Jah a portrait of Warren Lewis, in King Bunny an image of Jack Lewis, and in the pompous frog, their father Albert Lewis, whose love of politics is reflected in this work. We are also introduced to Mr. James Bar (a bear) and to the owl Puddiphat, owner of the numerous Alhambras, music-halls of whose performances, “the amiable” Phyllis LeGrange and Rosee Leroy, we learn only a little, when with their majesties, the party partakes of “cold ham & chicken, salads, oysters & other delecacies [Sic: Hooper carefully reproduces Lewis's juvenile spelling errors].”

In “The Locked Door” (which is accompanied by the fragment “Than-Kyu”), the story commences “since the famous Old Clique of Boxen had been broken up to give place to another of younger and more energetic members.” (The cool and faintly ironic tone of this passage, written by a boy perhaps twelve years old, is to recur in the opening chapters of That Hideous Strength, when the political machinations within Bragdon College are recounted.) One of the major features of “The Locked Door” is a detailed description of the music-hall presentation, “The Three Loonies,” in which their Majesties and Lord Big are impudently parodied as “a hare, a negro, and a toad.” (Readers will recall that the parodied subjects are a rabbit, an East Indian, and a frog). As it turns out, their Majesties are amused, but Lord Big is not!

Another feature––early evidence of the rather boyish but robust element of humor still evident in Lewis’s later works––describes a prank in which Lord Big’s mattress is stuffed with golf-balls by the mischievous Mr. Bar. A third is the invasion of the Tracities––bastion of the Chess, of whom Jack Lewis says in “The Chess Monograph” that “Just as the Jews were treated in England at the same time; so were Chessmen treated” (50). That is, they were “few; scattered, unhoused, hunted, disliked, and pennyless” in the “12th, 13th, 14th centuries.” King Flaxman settled his people in Clarendon, where he founded the first Chessary, at the expense of “the natives” there. The Kingdom thus established has by the time of Hawki V and Benjamin VII become master of much of Boxen’s shipping. I won’t spoil the suspense by describing the resolution of this famous battle, but I will report that the Little-Master administers a thrashing and a dunking to the unrepentant Bar, who reappears none the worse in the saloon of the Puffin where “the table, on which was a salmon & a tinned tongue, was laid for four” (142).

The third novel, “The Sailor,” describes the relationship between the eager young ship’s officer, Mr. Cottle (a grey Persian cat) and our old friend Mr. Bar, ship’s paymaster of HMS Greyhound. The story begins with Mr. Cottle as a would-be reformer and Mr. Bar as the delightful rascal we have already met. By a remarkable twist, it ends with––but why spoil the fun? In this third novel the young author’s talents are firmly in hand and the story is detailed, truly funny, and psychologically convincing.

As Fr. Hooper’s introduction suggests, this boyish world exerts its own fascination: it is more or less consistent, and creates a strong conviction of its reality. Carried along by the young narrator’s art, one is inclined to forget that this is the work of a schoolboy: the conversations, the descriptive passages, the details of sea-voyages, weather, the towns, theatres, dinner-parties, intrigues, pranks, characterizations, and geography, carry one into an Edwardian world as seen through the eyes and imagination of one of its keenest if most youthful observers. Students of the Narnian Chronicles will find here, in germ, many of the elements which give those works their distinctive flavor. What they will not find, as Lewis told us, is the beauty, which makes the Chronicles the masterworks they are. The stab of supernal Joy which greets the reader on every page in Narnia is absent from Boxen. But the spark of genius is there, ready to start alight.