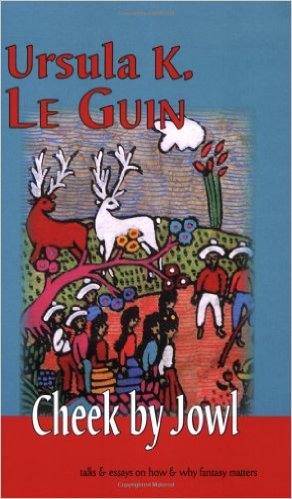

Cheek by Jowl

Cheek by Jowl. Ursula K. Le Guin. Seattle: Aqueduct Press, 2009. 149 pp., $16.00 (softcover). ISBN 978-1-933500-27-0.

Reviewed by David Bratman

[This review originally appeared in Mythprint 47:3 (#332) in March 2010.]

A new essay collection by Ursula K. Le Guin is as important an event as a new novel or poetry collection from her. This small book, from a small press, deserves not to be overlooked. Described on the cover as “talks & essays on how & why fantasy matters,” it does not reprint her famous 1970s essays on the subject, but carries on the argument to current time: almost all the contents date from the last decade. Le Guin is still fulminating against what she once called “Poughkeepsie fantasy,” but she now phrases it in terms of the junk fantasy of recent times, the ones about “the Good guys and the Evil guys [who] are hard to tell apart since all of them use violence as the response to all situations.” The Lord of the Rings is frequently cited as the antidote to all this mouthwash. I cheered when Le Guin writes that, despite the superficial faithfulness of the films, “the focus on violent action and the interminable battle scenes overshadow and fatally reduce the moral complexity and originality of the book.” Le Guin gets it, in a way apologists for the film do not. (Elsewhere, she has a similar complaint to make about Disney’s version of Bambi.)

Several other themes recur in these essays. She cites fairy tales as her earliest influences, long before she set herself up as an author, and hence an influence that one may remain unaware of unless closely examined. Perhaps this may also be so for others. She warns against reductionist criticism, rationalizing fantasy away as satisfying the author’s personal psychological needs (and she places readings of The Lord of the Rings as a Catholic apologia or a Great War expiation into that category). She chides critics who dismiss fantasy as childish, or who discuss it while remaining unaware of its genre. The Harry Potter books may be delightful, but a school for wizards was not – as many critics claimed – a unique and unprecedented idea, ruefully says the author of A Wizard of Earthsea. All fantasy critics, she says, should read Tolkien’s “On Fairy-Stories.” You can disagree with it, but you can’t ignore it.

She interestingly contrasts fantasy with realistic fiction for older children. The latter is mostly didactic message fiction. It spoils the reader into looking for messages in everything. When asked by child readers in those terms, she replies, “I’m not an answering machine – I don’t have a message for you! What I have for you is a story.” For fantasy is a branch of myth: it’s stories that tell us who we are. And it does so by taking us out of ourselves. Realistic children’s fiction is mostly relentlessly quotidian. Fantasy can “include the nonhuman as essential.”

This explains the longest essay, which takes up about half the book. It’s the title essay, a taxonomy of animals in children’s literature, both realistic and fantastic stories. (“Cheek by jowl” is, of course, how humans and animals live, in societies that do not artificially separate them.) Le Guin surveys about thirty books, classic and new, famous and forgotten. Her highest praise goes to the realistic books describing animals’ lives from their own, animalic perspective, because like fantasies they take us into the nonhuman. These include not just the famous tales of horses and dogs and deer, but one about a cow and another about a chipmunk.

Moving towards more anthropomorphic stories, Le Guin becomes more critical. She is cautious but forgiving of classic writers like Grahame and Kipling, but she inserts insightfully ruthless barbs into some well-loved authors. Pullman’s His Dark Materials, she points out, despite appearances is virtually animal-less. His daemons are wish-fulfillment fantasy pets that don’t even have to be fed. Adams’ Watership Down, though it claims to be realistic about rabbits, is to Le Guin deeply dishonest here, a rigidly sexist story where even the good guys are militaristic, and in both respects it is anthropomorphic. (Though I love that book, I must admit this criticism is well-taken, except for one thing: of the acquiring of does from another warren, Le Guin says, “That the females might have any voice in the matter is not even considered,” which is flatly untrue. They want to go, they take initiative, and they are active if secondary partners.)

But it’s not all negative at this end of the animal story. Charlotte’s Web and The Sword in the Stone, by the two Whites, are true to their own premises and face the tough moral questions about animal-human relationships unflinchingly. She even has a good word for Through the Looking-Glass as a cat story.

This essay has nothing to say about her own work – catwings, she decided, were out of the essay’s remit – because Le Guin is a true critic and not just a me-me-me author. Yet elsewhere she has new and interesting things to say about her own work. “The Poacher,” she says, is a story built on dredging out those unexamined childhood fairy-tale influences. In an essay on A Wizard of Earthsea, she talks about writing for older children without prior experience, and about the difference between intentional decisions, like making her wizard non-white, and unconscious creation of implications, like citing the myths surrounding him, which she intended as purely a trick to create resonance, but which generated whole new stories afterwards.