Tales Before Narnia

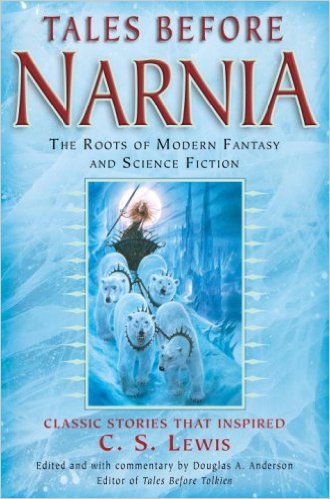

Tales Before Narnia: The Roots of Modern Fantasy and Science Fiction. Ed. Douglas A. Anderson. New York: Del Rey, 2008. xi + 339 pp. Trade Paperback. $15.00. ISBN 978-0-345-49890-8.

Reviewed by John D. Rateliff

[This review originally appeared in Mythlore 28.1/2 (#107/108) (2009): 167–71.]

Following in the footsteps of Tales Before Tolkien [2003][1] — an admirable collection which brought together stories by writers who had influenced Tolkien, or whom he admired, or who anticipated his work in some way — Tales Before Narnia casts similar light on the antecedents of C.S. Lewis’s creative work. The focus here is more narrowly drawn, with Lewis’s specific connection with each of these twenty items carefully laid out in the headnote to each individual poem or tale. Despite the title, it must be stressed that this book is not limited to Narnia, or even Narnia-centric, but (as the Introduction clearly sets out) includes works relevant to the whole of Lewis’s fiction, which Anderson interprets broadly to include fourteen of Lewis’s books, from The Pilgrim’s Regress and the space trilogy to Till We Have Faces, The Great Divorce, and even The Screwtape Letters.

Interestingly, the arrangement here is chronological — not in the order in which these stories were published, but the order in which Lewis first encountered them, in so far as this can be determined. Thus the collection’s first entry is the poem “Tegnér’s Drapa” [1849] by Longfellow,[2] which Lewis read when eight years old and in his autobiography held had been his first introduction to “the northern thing.” Although unorthodox, I think this system is proven wholly effective by the results, putting early and enduring influences up-front in the book and those which derive more from personal acquaintance in adulthood towards the latter half of the volume.

As for the stories themselves, the pagan North as mediated through Longfellow is immediately followed by E. Nesbit, a childhood favorite of Lewis’s and perhaps the major influence on Narnia. Indeed, the story included here, “The Aunt and Amabel” [1909], is so transparently a source for The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe that it tells of a little girl who enters an old wardrobe and discovers a magical world within, with her starting point being known there as Bigwardrobeinspareroom (cf. Mr. Tumnus’s mistaking the names of Lucy’s home as ‘Spare Oom’ and ‘War Drobe’). Next comes the classic Hans Christian Andersen tale The Snow Queen [1845],[3] in which the tall white queen of the snow carries away a cynical boy on her magical sledge to her palace of ice, the undoubted inspiration for Narnia’s White Witch. This in turn is followed by an excerpt from George MacDonald’s Phantastes, the first book Lewis read by the writer he considered “my master.” Unfortunately, while Phantastes is probably MacDonald’s greatest work, the excerpt given here[4] does not fully display its merits, being an inset story read by the main character at one point; the opening section or closing chapters of the novel would have better conveyed MacDonald at his best. After the MacDonald comes one of the classic literary fairy-tales, or märchen, of German Romanticism, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué’s Undine [1811], the tale of the tragic love between a human knight and a beautiful but soul-less elemental, the water-spirit Undine.

Next up come two Screwtape antecedents. The first is excerpted from a book (Letters from Hell) for the English translation of which George MacDonald provided the Introduction [1884]; the Hell described therein rather resembles the grey suburbs of The Great Divorce. The second is more oblique, and a good example of Anderson’s detective work. In the aforementioned Introduction, MacDonald mentions having heard of a book from the 1650s called Messages from Hell or Letters from a Lost Soul. MacDonald admits to never having seen the book, nor was Lewis himself ever able to trace it. Anderson, however, has tracked down a Screwtapish set of dialogues called Infernal Conference: or, Dialogues of Devils, a once fairly well-known book from 1772, and reprints a lively exchange from it that is, at the least, an anticipation and parallel to Lewis’s book.

The tales that follow from this point fall for the most part into two categories: stories by writers Lewis admired but who were not direct influences on his own fiction, and pieces by writers with whom he had some strong personal connection. In the first block we find Scott, Dickens, Morris, Stevenson, Kipling, and Chesterton. In the second group we find his fellow Inklings Owen Barfield, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Charles Williams, as well as Roger Lancelyn Green and William Lindsay (Bill) Gresham.

To deal with the first group first, here we have a half-dozen authors popular in their lifetimes (in most cases, wildly popular) but who, with the exception of Dickens, have fallen in critical esteem since their deaths —unfairly, Lewis thought. Anderson gives us a ghost story apiece by three of these men, each of which strongly conveys the characteristic flavor of its author: Scott’s “The Tapestried Chamber” [1828] is as realistic as possible, Dickens’s “The Story of the Goblins Who Stole a Sexton” [1837] fanciful and comic with a strongly drawn moral, and Stevenson’s “The Waif Woman” [1892], the most interesting of the three, a vivid saga-tale of the vengeful dead set in 10th-century Iceland. In Morris’s “A King’s Lesson” [1886] we have a sort of socialist fable critiquing feudalism, while Chesterton’s “The Coloured Lands” [1925][5] is an extravagant little Chestertonian parable of “Mooreeffoc” celebrating what Tolkien called Recovery. Finally, Kipling’s “The Wish House” [1924], although marred by his decision to write much of it in Sussex dialogue, is a remarkable story that anticipates by a decade or so Charles Williams’s chief theological teaching, the doctrine of exchange — i.e., that we could literally “bear one another’s burden’s,” agreeing to feel another’s pain or fear so that the original sufferer be spared that anguish. Kipling works this out in terms of folk-lore rather than theology, but it is to be hoped that someone will investigate the possibility that Williams might have originally derived his idea from popular fiction rather than theological speculation.

In the second group, Barfield’s “The Child and the Giant” [1930] is an Anthroposophical fairy-tale, an enigmatic little story with an underlying message about self-realization. Williams’s “Et in Sempiternum Pereant” (“And May They Be Forever Damned”) [1935] features Lord Arglay from Many Dimensions [1931] encountering a damned soul in an abandoned country cottage which has a basement stair leading directly into hell; it reads rather like Williams’s attempt to write a Wm. Hope Hodgson story.[6] Those Mythopoeic Society members who enjoy Williams’s fiction will welcome having his only short story — so far as I know, only reprinted once before, in Boyer & Zahorski’s Visions of Wonder: An Anthology of Christian Fantasy [1981] — available again. And as for Tolkien’s “The Dragon’s Visit” [1937], this is an unalloyed pleasure: one of Tolkien’s best poems, available again in its original form, in a font size larger than could be squeezed into the margins of The Annotated Hobbit (revised edition).

The one piece published in Tales Before Narnia which has never seen print before is a chapter from Roger Lancelyn Green’s The Wood That Time Forgot [circa 1945], which Lewis acknowledged as one of the direct inspirations of Narnia. Despite repeated attempts, Green was never able to find a publisher for his story, making this its first appearance. Its Narnian affinities are not very evident from this brief excerpt, but perhaps its appearance here will help lead to publication of the whole at long last, so that the details of Green’s contribution to Lewis’s series can at last be made clear.

Perhaps the most surprising figure included in this collection from among Lewis’s acquaintances is William Lindsay Gresham, Joy Davidman’s other husband, and the father of Douglas and David (who, as Lewis’s stepsons, ultimately inherited the Lewis Estate). It is usually overlooked in Lewis biographies, in which Gresham tends to make a brief off-stage appearance as a sort of stage villain, that Bill Gresham was a talented writer in his own right, a friend of Robert Heinlein’s and member of the science fiction community of his time. As for the story itself, “The Dream Dust Factory” [1947] combines Tolkien’s “escape of the prisoner” with a sort of Biercian “Owl Creek Bridge” motif in which a brutalized convict escapes into his imagination to avoid the horrors of his situation, only to lose touch with sordid reality altogether in the end (there’s a reason they used to call it “stir-crazy”).

Finally, we have two stories which did strongly influence Lewis. In “First Whisper of The Wind in the Willows” [1907] we have the original letters written by Kenneth Grahame to his son “Mouse” telling the familiar story from the point of Toad’s imprisonment to the end, recounted here with greater immediacy and in much less polished prose than the published book. First published in a little booklet in 1944,[7] almost a decade after Grahame’s death, this earliest form of the story has long been unavailable; its reprinting here reinforces the point made by Anderson of Grahame’s influence on Narnia’s Talking Animals, especially the Beavers in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.[8] And in C.F. Hall’s “The Man Who Lived Backwards” [1938] we have a real discovery. Lewis acknowledged in his preface to The Great Divorce that one idea he used in his book came from a science fiction story he’d read several years before, the title and author of which he no longer remembered. In a remarkable feat of research, and a real contribution to Lewis studies, Anderson has found the story and here makes it available to a wide audience for the first time.[9]

The inclusion of Hall’s and Green’s stories alone should mark this book as one everyone seriously interested in C.S. Lewis’s work will want to buy, while the inclusion of the Grahame and the Tolkien should extend the book’s appeal to all lovers of fantasy. And while it’s tempting to second-guess the selection — why are H. Rider Haggard and David Lindsay not represented?[10] — I’m sure that no lover of the Inklings’ works will be familiar with all the tales Anderson has gathered together here, many of which he has rescued from obscurity. A final selling point, if one is needed, comes in the form of the highly useful Recommended Reading section at the end, which gives brief evaluations and highly selective bibliographies of the authors included in this volume (all save Longfellow) and many more besides, in many cases enlivened with notes regarding Lewis’s opinion of or debt to each. This eleven-page section is packed with information, a good example of Anderson’s hallmark ability to say a lot, in highly readable style, in very little space. Dare we hope for a third volume in the series?[11]

1. In addition to Tales Before Tolkien, which demonstrates the great diversity in the fantasy tradition before Tolkien’s arrival on the scene, see also Anderson’s similar collections Seekers of Dreams: Masterpieces of Modern Fantasy [2005], which ranges from as far back as William Morris and Bram Stoker to as contemporary as Jonathan Carroll and Verlyn Flieger, and H.P. Lovecraft’s Favorite Weird Tales [2005], which brings together Lovecraft’s personal favorites from among both literary and pulp horror stories.

2. Which contains the famous lines “I heard a voice, that cried, / ‘Balder the Beautiful / Is dead, is dead!’”

3. Best known to many of my generation from the award-winning animated version, much admired by the great Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki, that was shown on television throughout the 1960s but afterwards dropped out of view. I suspect I am only one among many whose first encounter with Wagner’s music was through this feature-length cartoon (it was years before I discovered that what I knew as “The Snow Queen’s Theme” was better known as “The Ride of the Valkyries”), made in Russia in 1957 and dubbed into English in 1959. [For more on the influence of Andersen's Snow Queen on the White Witch, see Jennifer L. Miller's article in this issue. -Ed.]

4. The same excerpt has been published separately once before, by Lin Carter in his 1973 anthology Great Short Novels of Adult Fantasy, Volume II (part of Ballantine’s acclaimed Adult Fantasy Series), where Carter gives it the name “The Woman in the Mirror.”

5. Note that this is the title tale which gave its name to the posthumous Chesterton collection [1938] from which Tolkien drew all his Chesterton quotes when writing “On Fairy-Stories.”

6. See in particular The House on the Borderland [1908].

7. An event noted by J.R.R. Tolkien at the time, who wrote in a letter that he “must get hold of a copy” (Letters of J.R.R.Tolkien, page 90).

8. [See the review later in this issue of the Norton annotated Wind in the Willows, which also reprints these letters. -Ed.]

9. This has the added effect that we can now not only see how Hall’s story influenced The Great Divorce but also discover its impact on The Dark Tower as well in that work’s opening discussion of the impracticalities of physical time travel.

10. Presumably they are omitted, despite their obvious influence on Lewis, because both are already covered in Anderson’s Tales Before Tolkien. If we think of the two books as companion volumes, as Anderson suggests in his Introduction to Tales Before Narnia, then the desire to avoid duplication makes sense.

11. One minor final quibble: though I by no means assume that a cover blurb reflects the views of the book’s author, the back cover copy’s claim that Lewis’s “influence on modern fantasy, through his beloved Narnia books, is second only to Tolkien’s own” seems to me to rather overstate Lewis’s legacy.