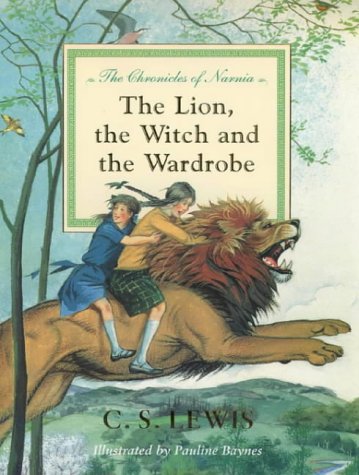

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

Lewis, C.S. The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. With color illustrations by Pauline Baynes. London: Harper Collins, 1991. ISBN 0-00-183152-6

Reviewed by Nancy-Lou Patterson

[This review originally appeared as “Aslan’s Country” in Mythlore 18.1 (#67) (1991): 56-57.]

Certainly the most beautiful edition ever published of Lewis’s superb fantasy, this book rejoices in eighteen wonderful color illustrations by the first and still best Narnian illustrator, Pauline Baynes, along with a reprint of her already well known fine color map of Narnia. Enclosing there are the endpapers, offering an aerial view of the moment when, with Aslan’s arrival, Narnia begins to emerge from the fixed imprisonment of a winter without Christmas to the freedom of a glorious spring where birds and animals play about the stone table where Aslan is to offer his life: this prefiguration of the Narnian Resurrection perfectly embodies the central metaphor of the book.

The color illustrations within are exquisitely refined and jewel-like. They not only repeat themes treated by the artist’s incomparable penwork from the original editions (here sadly marred by repeated copying, obviously not from the original drawings), but enlarge upon her vision, and consequently upon ours. The fundamental structure of the drawings also contains a powerful metaphor. Each is––partially––contained in a framing border, increasingly and variously breached as the events of the world within the wardrobe encroach upon the mundane world of the reader. Narnia is a world within, a place for the enactment of a psychodrama experienced by the various child visitors and vicariously, through our identification with them, by ourselves. That world spills into ours because, as we are told in The Last Battle, every place is a foothill of Aslan’s country.

It would be difficult to choose the most perfect of these wonderful paintings. I know from personal experience with others of her original works that Pauline Baynes miraculously paints these works at the same size as that at which they are reproduced, a remarkable achievement. But to fit our narrow format, I will mention some which significantly increase our visual knowledge of Lewis’s story. The illustrations entitled “She immediately stepped into the wardrobe,” which is based in part upon the very wardrobe so lovingly preserved at the Wade Center in Wheaton, reveals between the fur coats within, a glimpse of a winter forest with the light of a distant lamp gleaming minutely, like a star.

In “A few mornings later Peter and Edmund were looking at a suit of amour,” we are given a far more elaborate view than ever before of the interior of Professor Kirke’s house, which, Lewis tells us, “was so old and famous that people from all over England used to come as ask permission to see over it” (50). What we see is a view of “the Green Room,” evidently so called for its rich green draperies and a portrait of a lady in green, with ”beyond it … the Library” (53), filled with books and curious furnishings, at that moment before Mrs. Macready and “her party of sightseers” cause the children to take flight to the Wardrobe Room.

Although this volume contains a very bad reprint of the extremely delicate sketch of the Beavers’ “funny little house” on the dam, a larger version, rather taller, appears in the colored view of an elegant winter landscape, showing in detail the “glittering wall of icicles, as if the side of the dam had been covered allover with flowers and wreaths and festoons of the purest sugar” (68). The stone figures encountered by Edmund in the courtyard of the Witch’s castle also appear in ink but are rendered in color as noble beings locked in their cold enchantment, matching Lewis’s description of the “lovely stone shaped that looked like women” and “the great shape of a centaur and a winged horse and … a dragon” (90).

My personal favorite in the series depicts Father Christmas giving his solemn gifts, perfectly embodied in his hooded robe, “bright as hollyberries” (100), offering Peter a sword and a shield with “a red lion, as bright as a ripe strawberry” (101). In a delicate touch, the wooden sleigh is carved with design reminiscent of those on the wardrobe, as befits the remark of Lewis about Father Christmas that “though you see people of his sort only in Narnia, you see pictures of them … even in our world the world on this side of the wardrobe door” (100). This image, so important for the symbolism of Narnia, and absent from the original illustrations, here appears as the numinous icon Lewis intended in the text.

Many of the illustrations repeat, in color, scenes already strongly evoked in penwork, but a moment which––of course––surpasses that of the advent of Father Christmas, is the romp of the resurrected Aslan, here gloriously shown just as the magnificent Lion leaps beyond the frame of the picture into pure air, overarching a Narnia lovely in the garments of spring, past “wild orchards of snow-white cherry trees; past roaring waterfalls … up windy slopes … and across the shoulders of heathery mountains” (152-53).

The series concludes with an enchanting medieval vision of the four children seated in equal majesty upon thrones amongst their loving subjects, while in the foreground we see “the mermen and the mermaids swimming close to the shore and singing in honour of their new Kings and Queens” (168), and in the background “the wonderful hall with the ivory roof and the west wall hung with peacock’s feathers” (168) which prefigures eternal life. One only hopes that every one of the remain six volumes of the Narnian Chronicles will appear in due time with color illustrations by Pauline Baynes, adorning them too with refined evocations of Lewis’s enchanting prose, making visible in a world jaded and engorged by the rancid images of our excessive era, her ever refreshing vision of the things that cannot be tarnished and will never fade.