1998 Tolkien Calendar

The 1998 J. R. R. Tolkien Calendar. HarperPrism, New York. ISBN 0-06-757487-4. $11.95 U.S./$17.00 Canadian.

(This review originally appeared in Mythprint 34:11 (#188) in November 1997.)

Reviewed by Paula DiSante

In the last several years the Internet, and the number of those users accessing it, has burgeoned in an astonishing fashion, passing from a mind-numbing information blitz into an accepted fact of modern life. Little wonder that much data and imagery appear over and over on countless home pages. Many web page authors, either out of ignorance or arrogance, merrily violate copyright law by pirating the images of works by artists and illustrators. These web authors “publish” these works on the Net, where the images are then accessed by thousands, even millions, of Web surfers, who in turn do a little pirating of their own. This is more often than not done without the permission of the artists.

What has this to do with the 1998 J. R. R. Tolkien calendar? For starters, many, if not all, of the paintings in the new calendar have been on the Internet for months now. So there are almost no surprises awaiting any purchasers of the calendar who also have done any web surfing under the key word “Tolkien.” Not that there was much to spoil in the way of visual surprises. The 1998 calendar is lackluster at best, and will not be remembered as a high water mark in the over 25-year history of the Tolkien Calendar. A few paintings do manage to distinguish themselves, however, so the calendar is not a total wash-out.

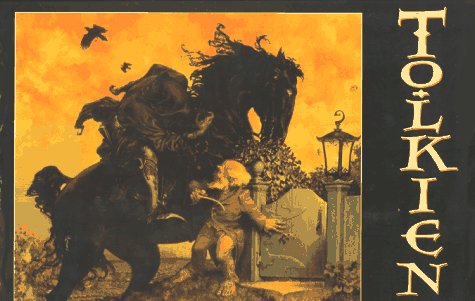

The cover painting is an oldie by Stephen Hickman of Gaffer Gamgee menaced by a Black Rider. It is a dramatic painting, certainly better than most in the calendar. But it also hails from the 1980′s, and any Tolkien illustration fan will have surely seen it many times by now.

The style of January’s “In the House of Beorn” by Capucine Mazille is quite delightful. A watercolor painting on rough textured paper, the hues here are rich and jewel-like. Mazille’s style is most definitely the sort found in children’s book illustration, and it works very well. Bilbo, Gandalf and the dwarves crowd around Beorn’s table, with the host’s beloved animals keeping watch over the proceedings. Beorn is shown as exotic and mysterious, not quite the way he’s described in the book, but a commendable depiction nonetheless.

February’s “The Nazgûl” by Lode Claes is suitably unsettling, showing five Nazgûl haunting a low hilltop. But it has an odd quirk: the Nazgûl seem to be presiding over a moonlit snowscape. If this is supposed to be Weathertop, it does not follow the text at all. If it is not supposed to be snow, then there is entirely too much light coming from the moon. But that observation aside, it is a chilling mood piece, even though lacking a bit in the drama department.

Inger Edelfeldt’s brown and green and gold “Treebeard” (March) is certainly not one of her best. Edelfeldt shows Treebeard savoring a bowl of his favorite drink. The glow from the bowl is not as convincing as it might be–in fact, the contents resemble bland split pea soup. But Treebeard’s moss-like beard is interesting–unfortunately, much more so than his face.

April’s “A Pleasant Awakening” by Carol Emery Phenix is far from pleasant–it’s downright wretched in execution. Frodo and Gandalf are painted so clumsily as to be embarrassing, especially the Gandalf. The one redeeming feature is the light on the golden leaves outside the window. Next!

May’s “Treebeard and the Ents” by Timothy Ide, is essentially (although tinted with color) an intricate pen and ink drawing. Treebeard has to be one of the most controversial of Tolkien’s creatures, as far as how he looks in the imagination of readers. Ide’s depiction is no exception. His ents are gigantic, far taller than described in the text. Merry and Pippin, on the other hand, stick pretty close to Tolkien’s visual characterization, although the hobbit on Treebeard’s right shoulder (in the center of the painting) does bear a strange resemblance to Bette Midler from her days as “The Rose.”

An oft-portrayed scene, June’s “Gandalf and Pippin” (by Luca Michelucci) race toward Minas Tirith aboard Shadowfax. Although the silver-gray stallion is acceptable, hobbit and wizard are miserably painted, making this a forgettable, regrettable piece.

July, “Bilbo Flies on Eagle’s Wings” by Gerd Renshof and Ron Ploeg. The last thing the bird in this picture looks like is an eagle. Instead, Bilbo seems to be perched atop a gigantic swallow. Still, if considered as a “children’s” illustration, this painting does have some charm, as well as a unique (and vertigo-inducing) high-angle perspective far above the mountains.

August, “The Mûmak of Harad” by Cor Blok. This is the best painting in the calendar. Tolkien was said to have liked Blok’s style, and it is easy to understand why. Blok’s minimalist, “primitive” approach has an uncomplicated childlike quality. But beyond the simple surface, this painting has a lot of emotional weight–the gravity and terror of battle with a force of Nature much bigger than any these warriors has ever encountered. The textured surface of the piece, as well as the limited colors (mostly brownish greens accented with red) makes us as aware of the surface–the “artifice”–as of the image itself. A great painting.

September, “Gandalf’s Escape from Orthanc” by Fletcher. There is no mistaking that this bird is an eagle. But it is a pity that the artistic effort so evident in the head of the eagle is not matched in any other part of the painting. This is visually dull and boring, and Orthanc totally unlike its textual description. Gwaihir’s “harness” from which Gandalf grapples with reins (!) is utterly bizarre and also non-textual.

October, “Gollum held Captive by the Elves.” Inger Edelfeldt redeems herself with this work, mostly because of the splendid Gandalf in the scene. The costumes of the Elves are appropriate and worked with skill. The Gollum might make some readers grumble, but others will be more than satisfied. And the woodland setting, with its softly glowing light and smattering of wildflowers, is especially well painted.

November, “The Lord of the Nazgûl Enters the Gates of Gondor” by Fletcher. If Blok’s painting is the best of the bunch, this one, by sheer dint of its lack of logic, is the worst. The Nazgûl looks like nothing more than a badly carved equestrian statue, with all the malice and fear-inducing qualities of a naked department store mannequin. The walls of the city look about as substantial as a vanilla wafer, and the “gate” seems to be exploding into a rain of Lincoln Logs. But the oddest feature, on the left of the piece, is the bare-armed, doubled-over man, a poorly painted arrow skewering his chest. Strangely, the look on this mysterious man’s face, presumably meant to be agony, comes off as one of raucous laughter. Nothing in this painting makes any sense, and has little connection to the scene as Tolkien wrote it. A world-class disaster, this.

December, “The Prancing Pony.” Another of Timothy Ide’s tinted, intricate pen and ink drawings. Frodo stands atop a small (probably far too small to dance on) table, to the amusement of the patrons. Strider, puffing his pipe, watches from a corner. Ide does a good job of capturing the differences between the “big people” and the hobbits. His costuming of the characters is particularly good, if (in a few instances) a bit Dutch. But Ide’s perspective and use of space is solid, and the colors he uses are just right.

The 1998 calendar is another hit and miss effort. One can continue to hope for calendars that have a more clear-cut visual purpose and direction. This would best be achieved by actually commissioning artists each and every year to render new works, and not dredge up old paintings simply to fill out the complement of months. Get it for your collection, but don’t expect spectacular things from this year’s model.